Commentary by Cory Doctorow

The internet succeeded where other networks failed. Where there were once many nets – cable, phone, leased-line – now there is just The Net, which runs over many of the same substrates, but which has subsumed them all. The secret of the internet’s success was to reduce, reduce, reduce. If we can’t agree on the right way to do x, perhaps we can agree on the right way to do y, upon which we might someday build x? Take a smaller step, agree on a foundation, keep decomposing a seemingly monolithic technological project into ever-smaller pieces until we find one that we can all agree on. Build that, then do it again, finding another step that everyone can get behind.

The only way to eat an elephant is one bite at a time.

It worked. Sometimes, we even figured out that we didn’t need to build the whole thing – sometimes a ‘‘partial’’ solution was sufficient. As one of Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies has it: ‘‘Be the first person to not do something that no one else has ever thought of not doing before.’’

That’s what happened with email. For a long time, the Email Problem was how to validate senders, so that if you got an email from someone purporting to be me, you could be sure that it wasn’t an impersonation.

This would indeed be a wondrous thing, but to make it work, we would all need to agree upon an authority who would decide who was whom. We’d need a DMV for the Global Internet to issue Information Superhighway Driver’s Licenses to everyone in the world. Designing such an institution is a tall order, and we’re no closer to resolving this today than we were in 1982, when RFC 822, ‘‘Standard for ARPA Internet Text Messages,’’ was first published.

That standard basically says, ‘‘Let’s do the messaging now, and figure out the identity later.’’ Forty-one years later, we have the messaging, and we’re still working on the identity! All the identity-based email systems that competed with the standard withered on the vine. The standard thrived.

Be the first person to not do something that no one else has ever thought of not doing, and the world will beat a path to your door.

Today, we’ve lost the art of eating elephants. Rather than taking a single bite out of the elephant, we try to fit the whole thing in our mouths at once. No wonder we keep choking on it.

(For avoidance of doubt: we shouldn’t eat elephants in the real world; this is just a metaphor. I am an elephant vegan and I encourage you to be one as well.)

Take the debate about regulating social media: should we allow bullying? Hate speech? What about bots? Making progress on these subjects depends on us first finding consensus on the definitions of ‘‘bullying,’’ ‘‘hate speech’’ and ‘‘bot.’’

That would be great, but I’m not holding my breath. I want a better internet now, not years down the road. I’ll happily take a smaller bite. Even a small victory beats an endless stalemate.

Here’s something I think we should all agree upon: when a willing speaker wants to say something to a willing listener, our technology should be designed to make a best effort to deliver the speaker’s message to the person who asked to get it.

I hope this is self-evidently true. When you dial a phone number, the phone company’s job is to connect you to that number, not to someone else. When you call Tony’s Pizza, you expect to be connected to Tony’s Pizza – not to Domino’s, not even if Domino’s is willing to pay for the privilege.

When you use your TV remote to tune into CNN, you don’t want your cable operator to show you Fox instead – not even if Fox will pay them to do so.

If you follow someone on social media, then the things that person says should show up in your timeline.

That is not a radical proposition, but it is also not the case today. Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, YouTube and other dominant social media platforms treat the list of people we follow as suggestions, not commands. When you identify a list of people you want to hear from, the platform uses that as training data for suggestions that only incidentally contain the messages that the people you subscribed to.

There are various reasons for this, but they all boil down to the platform shifting value away from its users to its shareholders. Obviously that is the case with ads: the volume of ‘‘sponsored posts’’ that enshittify your feed is titrated to be just below the threshold where the service becomes useless to you.

But there’s another group of people who can pay to reach you – the people you’ve chosen to follow. When you subscribe to a performer, or a news outlet, or a political group, they have to pay to ensure that the things they publish show up for you. The platforms have cute names for this danegeld (‘‘boosting,’’ etc), but it boils down to the phone company telling Tony’s Pizza, ‘‘If you don’t pay us extra, then every time someone calls Tony’s, we’re going to connect them to Domino’s.’’

Thus the enshittification of your feed is only partially about showing you ads: it’s also about making the people you want to hear from pay to reach you.

This shouldn’t be allowed. The services should make their best effort to deliver messages from willing senders to willing receivers.

This principle can be generalized to other kinds of online services. When you search for a product on Amazon, the first result should be the product you searched for, not an Amazon own-brand clone of that product, or the product of a rival that paid for the privilege of being at the top of the results.

The argument about whether Amazon should be cloning its sellers’ products is a complex and thorny one. The question of whether Amazon should trick you into clicking on something you didn’t search for is much simpler.

They shouldn’t be allowed to do this. It is an ‘‘unfair and deceptive practice’’ and it is already illegal under Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act.

We can apply this to other kinds of search. When you search for a band on Spotify, you should get that band’s music, above suggestions for other bands whose labels handed over payola. When you search for an album on Spotify, you should get that album, not a playlist with the same name as the album, but that includes soundalikes or ‘‘suggestions’’ that generate additional revenue for Spotify.

Same for Google. There’s a long-raging series of legal cases and controversies over whether Google ‘‘self-preferences’’ and whether this should be permitted. For example, when you search for a restaurant and Google shows you its own reviews ahead of TripAdvisor’s or Yelp’s, is this because Google sincerely believes you will find its reviews more useful than those of its rivals?

This is an almost metaphysical question, which requires that we peer into the psyches of Google’s product managers and engineers to determine the sincerity of their beliefs about the relative merits of different review sites.

Sometimes we can do that. In the case of Yelp, there’s a smoking-gun internal email chain in which a Google engineer complains to their boss that they have been ordered to put Yelp’s reviews below Google’s, even though Yelp’s are better. But as hubristic as the tech giants are, we can’t rely on them making a habit of putting their plans to deceive their customers in writing.

Meanwhile, there’s a much simpler question to resolve: when you searchfor ‘‘Yelp reviews of Tony’s Pizzeria,’’ the first result should be the Yelp link, not Google’s. That is a bite of the elephant that we can all agree on taking first, I hope!

Everything old is new again.

This principle – that services should make their best efforts to deliver messages between willing senders and receivers – is one of those minimum agreements that we built the internet on, all those years ago.

Back then, we called it ‘‘the end-to-end principle,’’ or ‘‘E2E’’ for short. As self-evidently just as E2E is, businesses are endlessly tempted to break it. Services want to decrypt your messages to make sure you’re not infringing copyright – or maybe they just want to find out what you’re talking about so they can target ads to you, or sell your data to a broker.

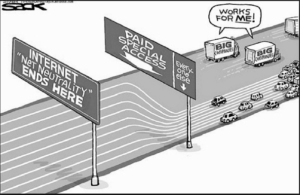

Internet service providers hate E2E. They want to be able to practice ‘‘network discrimination’’ whereby they charge businesses extra to have their packets delivered to you after you request them. Under network discrimination, Comcast could slow down videos from YouTube, Prime, and Netflix, while allowing the streams from Peacock (a far less popular video service owned by Comcast’s parent company, NBC Universal) to flow at maximum speed.

The opposite of network discrimination is net neutrality, Tim Wu’s useful coinage that is really just another name for the end-to-end principle.

We need net neutrality for services, too. If you subscribe to a newsletter, you should be able to tell Gmail that its messages are not spam, and thereafter they should never, ever, ever be filtered into your spam folder again.

The fact that there is no way to do this – no way to permanently and forcefully override Google’s algorithmic ranking system – is genuinely remarkable and shouldn’t be tolerated.

We can argue endlessly about whether Google should mark unsolicited donation-begging emails from politicians as spam – but if you ask for emails from a politician, I hope we can all agree that those messages should be delivered.

E2E is a rule that’s easy to follow, and it’s easy to tell if someone is violating it.

Figuring out whether Google’s spam filter treats unsolicited mail unfairly is hard. First, we have to agree on what fair is. Then we have to figure out if Google’s filter is deliberately unfair. Then we have to agree on what would make it fair. That’s a process that lawyers euphemistically call ‘‘fact-intensive.’’ I get a headache just thinking about it.

Contrast that with the simpler question: ‘‘Did I tell Gmail that I want to receive email from this sender, and, if so, did Google deliver it to me?’’ That is a much easier question to resolve. What’s more, if the answer is no, the solution is obvious: ‘‘Gmail, you must deliver emails from senders that your users tell you they want to hear from.’’

Likewise Amazon: determining whether Amazon showed you a ‘‘good’’ or ‘‘bad’’ product recommendation requires that we all troop over to Plato’s Cave and look over our shoulders at the true forms projecting their shadows on its wall. What a pain in the ass.

By contrast, ‘‘Did Amazon retrieve the product whose name or product number I typed into the search box?’’ is an easy question to answer, and again, if the answer is no, the solution is straightforward: ‘‘The first result for a search should be the product that most closely matches the thing I searched for.’’

(Yes, we can argue about how a typo should be handled, or what should be done about multiple products with the same name, but these are easier arguments to resolve than ‘‘Are the suggestions and ads that fill Amazon search results good or bad?’’)

We can apply this to app stores, too: ‘‘If I search for a specific app, the first result should be that app.’’ And of course, this is also something we can apply to social media: ‘‘If I subscribe to your feed, then when you publish something, it should show up in my feed.’’

Note that E2E depends on willing recipients. If a service like TikTok or YouTube or Facebook or Twitter wants to offer a priority-ranked feed, or a feed of suggestions, that’s a great option.

If we want those algorithmic feeds to be good, they need to compete with ‘‘the feed of things I asked for.’’ That has to be the baseline; otherwise companies can enshittify their feeds without worrying about damning comparisons between their recommendations and the stuff that you signed up to see in the first place.

Here’s one more thing to like about applying E2E to online services: it’s a rule that even small services can comply with.

Many of the proposals for social media regulation require enormous resources to comply with: capital, servers, and human moderators.

If we make these into legal obligations, then we freeze the internet in place, because only the firms that have grown to dominance, whose monopolistic power lets them extract vast profit from the rest of us, can afford to operate under that system.

By contrast, E2E is a rule that small providers can comply with just as easily as a large one. If your church group or car club wants to run its own Mastodon server, or its own email server, or a little web shop for its goods, making sure that the things that users ask for are at the top of their feeds and search results is trivial. Indeed, this takes less in the way of resources than suggesting other things that the user hasn’t asked for. This also applies to startups, co-ops and other smaller businesses and nonprofits who might be better stewards of your trust and patronage than the giant, entrenched corporations that run the internet today.

We probably do need rules about how the internet should work that go beyond E2E, and there’s no contradiction between making E2E our polestar now, while we figure out that other stuff.

Indeed, an end-to-end internet is one where our debates about everything else can take place, rather than going to spam, being buried under ads, or being filtered out of your feed.

Cory Doctorow is the author of Walkaway, Little Brother, and Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free (among many others); he is the co-owner of Boing Boing, a special consultant to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a visiting professor of Computer Science at the Open University and an MIT Media Lab Research Affiliate.

Source: locusmag.com, March 6, 2023