Duke University didn’t inform public about lead in Durham parks

By: Lisa Sorg

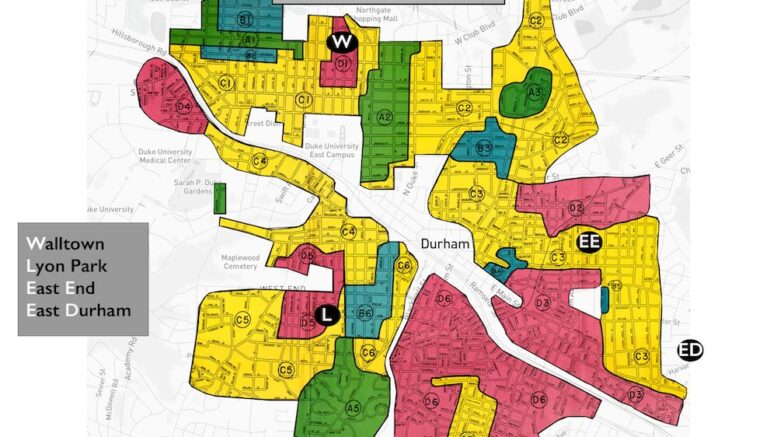

Soil at three Durham parks—Walltown, East End and East Durham (and presumably a fourth, Lyon Park)—contain levels of lead as much as six times the EPA hazard threshold for play areas, a Duke University study found. But the university and the Durham Parks and Recreation Department sat on the findings for months, sharing them in late May only after a Walltown resident stumbled upon the research paper online.

The four parks share some commonalities: From the early 1900s to 1940, they were home to city-owned incinerators, which burned lead-containing material. They are in historically Black neighborhoods and in former redlined areas where environmental racism and health disparities persist.

“The health risks associated with lead exposure pose a serious environmental justice problem, since marginalized and socioeconomically disadvantaged communities tend to have higher lead exposures than the rest of the population,” the study explains. “This trend is also evident in soil lead exposure, since many Black and other minority communities have been systemically driven to live and work in and around structures that serve as lead sources, such as older houses, gas stations, factories, and waste incinerators and landfills.”

Lead is a neurotoxin. Chronic exposure can cause permanent neurological and brain damage in children, who are especially vulnerable because they spend time outdoors and often put their hands in their mouths. Adults with high blood levels of lead can suffer from brain, kidney, heart and reproductive disorders.

“The delay in communicating the health risks posed by lead in the soil of Walltown, East End and East Durham Parks is a failure on the part of Duke and the City of Durham,” reads a letter from the Walltown Community Association to the city and the university. “Had residents not discovered the study on our own and taken the initiative to learn more, it is unclear when exactly the public would have been informed.”

In late May, a Walltown resident contacted the researchers, who presented their findings to the Walltown Community Association on May 22. Durham Parks and Recreation knew the research was happening; the study itself notes that the department granted access to the parks for the sampling. Parks and Rec reportedly also was aware “there were findings to share,” read a letter from Walltown Community Association to the city manager, “but have not communicated anything to residents in the three affected communities or the broader Durham public.”

The city received the information on June 1, according to an email sent to Walltown neighbors from City Manager Wanda Page. She shared an update with Walltown on June 7.

CBS17 first reported on Duke’s and the city’s delay in disclosing the information.

In the fall of 2021, with Parks and Rec’s approval, Enikoe Bihari, then a master’s student at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment, sampled soil at Walltown, East End and East Durham parks for lead. Bihari did not sample at the former Lyon Park incinerator site because of time constraints, according to the research paper. She is working out of state, according to her faculty adviser Dan Richter, and could not be reached for comment. Richter agreed to speak with NC Newsline, but did not respond to emails to schedule a time.

Bihari found that many shallow soils, no more than an inch deep, exceeded the EPA’s hazard thresholds for gardening, residential play areas and residential non-play areas: 100 parts per million, 400 ppm and 1,200 ppm, respectively.

In all three parks, the incinerators had been located in what are now “highly trafficked areas, such as grass fields, sports facilities, playgrounds, and picnic areas,” the study reads.

East Durham Park, 2500 E. Main St.

One hotspot with extremely high lead levels was found in the southeastern portion of East Durham Park. Concentrations ranged from 694 parts per million to 2,342 ppm in that area. These far exceed the EPA’s hazard threshold for gardening and for play areas.

“This is of particular concern because this field is adjacent to an apartment building, and residents appear to use this area to play, garden, and park their cars,” the study reads.

Underserved communities already face multiple risks from lead exposure in house paint. Because homes tend to be older in these neighborhoods, they often contain lead paint, which wasn’t banned for residential use until 1978.

That’s true in East Durham and in Walltown.

The EPA’s Environmental Justice Index combines demographics—the percentage of people of color and low-income households—with a single environmental factor, such as exposure to lead paint. Based on that index, neighborhoods adjacent to the East Durham Park rank in the 80th to 95th percentile in the U.S. in terms of potential lead exposure, according to the EPA’s EJ Screen. That means these areas rank higher than 80 to 95 percent of environmental justice neighborhoods nationwide.

State data show that people living in the census block groups near East Durham Park also experience rates of asthma hospitalizations three to four times the state average.

Walltown Park, 1700 Guess Road

In Walltown, concentrations ranged from 13 ppm— roughly background level—to 1,338 ppm in the center of the park, near the basketball goals and the horseshoe pits.

Walltown neighborhoods are in the 80th to 90th percentile for potential lead paint exposure. There are other environmental hazards nearby: The park is across the street from Northgate Mall, where historically there were oil and fuel spills from car maintenance shops. Rates of asthma hospitalizations in the neighborhood, which includes a section of Interstate 85, exceed the state average.

East End Park, 1200 N. Alston Ave.

At East End, levels ranged from 8 ppm to 1,364 ppm. On the south side of the park, lead levels were very high, likely because it is where the old city paint and sign shop operated.

Dilapidated buildings remain behind a chain-link fence on the property. However, because the ground is bare, “contaminated surface soil particles can be easily eroded by wind and water into the neighboring environment,” the study reads.

East End Park neighborhoods rank in the 90th percentile and above for lead paint exposure.

In addition, the census block groups near East Durham Park have rates of asthma hospitalizations and child mortality higher than the North Carolina average, state data show. The park is just two blocks east of the old Durham Gas Plant, where deed records show the property is contaminated with hazardous substances. At least one fuel spill occurred at the sign shop, according to state environmental records, and another two at the Honeywell facility, just east of there.

Lyon Park, 1228 Carroll St.

Until roughly 1950, the city of Durham operated an incinerator in Lyon Park at 1228 Carroll St., just north of Lakewood Avenue.

However, it’s likely that the soil is contaminated with lead, based on results from the other three parks, as well as separate and unrelated testing by U.S. Army contractors.

The Army is involved because it bought the property from the city in March 1957—after the incinerator had closed —and built a Reserve Center for training and vehicle maintenance. The center closed in 2012, and the property has been vacant ever since; the five and a half acres are enclosed by a 7-foot chain-link fence topped with barbed wire.

In 2021, contractors sampled soil at the site because the Army planned to sell the property to CASA, an affordable housing nonprofit, pending environmental testing. County records show that the federal government still owns the property.

Also in 2021, NC Newsline contacted the city of Durham about the sampling. In an email, Matthew Walker, the city’s community development manager, told NC Newsline the Army estimated the tests and the analysis would take at least two years, but that the city “would receive any future environmental/sample results.”

NC Newsline filed a public records request with the city for those results last week; the city responded that it has no documents about the sampling. The Army could not be reached by deadline.

But a brief report issued by the Army last September suggested that contaminants could be present in both the soil and groundwater at the Lyon Park site. Notably, fly ash, the byproduct of burning coal, is reportedly buried under the existing military equipment parking area. Before 1950, it would have been common for incinerators to burn coal.

Fly ash is considered to be a toxic waste because it can contain lead, arsenic, mercury, Chromium VI, and even uranium and thorium, both radioactive. Since it is contained under pavement at Lyon Park, it’s unlikely to be released to the environment. However, if the property were to be excavated, the pavement was to crack or cave, or if there are other hotspots of ash that could be exposed, that could present an environmental or public health threat.

“The amount and nature of the materials that were incinerated and the ash disposal process used at the time are unknown,” the U.S. Army report reads. “…The area of the historical incinerator requires additional evaluation.”

It’s uncertain if fly ash is buried at the other three parks, where the incinerators presumably also burned coal. Bihoki’s study noted that 500 truckloads of ash and cinder were transported from Walltown to Northgate Park as it was being built. However, “2,000 truckloads” of cinders and ash were also removed from the Walltown incinerator, which could have been used as fill at other similar sites, according to the study.

Coal ash is frequently used as “structural fill,” throughout North Carolina. State law requires owners of land where more than 1,000 cubic yards of coal ash have been disposed to file documents with the respective county’s register of deeds.

But state records don’t document all of the old “legacy” sites—coal ash dumps from the 1950s, for example—where such activity was virtually unregulated.

At Lyon Park, the Army is now further investigating possible contamination from the operation of the incinerator, including soil and groundwater sampling. Monitoring wells have been installed on the property, including at the incinerator site.

After the investigation is complete, the Army will conduct a second study to determine a clean-up plan, which would have to be approved by the NC Department of Environmental Quality.

Walltown demands; the city responds

As for the three other parks, the Walltown Community Association is demanding that the city and Duke University act quickly to protect the public from exposure to lead and any other contaminants by acting to:

• Prevent people from coming into contact in highly contaminated areas of the parks until they can be safely cleaned up and re-tested with a long-term monitoring plan;

• Hold community meetings to inform residents of the study’s findings and the risks;

• Conduct additional testing at the three parks, plus Lyon Park, Northgate Park and in northeast Durham, near the central incinerator. Tests should also be done in the park neighborhoods.

• Expand the county’s lead blood testing program to residents in these areas;

• Direct Durham Parks and Recreation to engage with the Duke researchers, the Durham County Health Department, and other relevant government agencies to present an action plan to the mayor in the next 90 days;

• Document and share what remediation and monitoring efforts have been conducted to date at each site in the next 90 days. Make this information publicly available.

• Publicly apologize to the affected communities

In response, City Manager Wanda Page wrote a letter to the Walltown Community Association saying the city is contracting with a state-certified consultant to conduct an environmental assessment of all four parks mentioned in the study.

City staff and the Durham County Health Department will also host information sessions with the neighborhoods near the parks, Page wrote.

“Once the City’s environmental assessment is completed, I will publicly share our planned next steps of how we will address any findings,” Page wrote.

Lisa Sorg is Assistant Editor and Environmental Reporter at NC Newsline.

Source: ncnewsline.com, June 12, 2023