By Eve Ottenberg

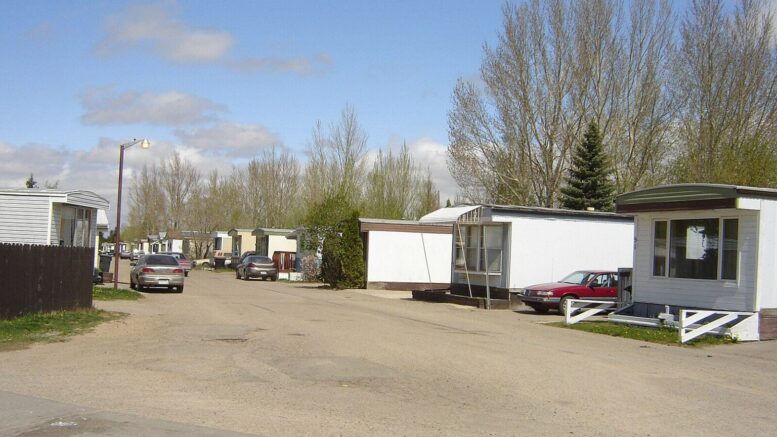

Roughly 20 million Americans live in trailer parks, and in recent years rents there, like everywhere, shot up. Since these tenants often cling to a lower rung of the socio-economic ladder, such rent hikes could easily spell destitution. That’s why Maine’s new law last year, giving trailer park residents the chance to purchase the land on which their mobile homes sit, is such a big deal. Because trailer tenants usually own their mobile home, but pay rent on their lot. So investors target these parks and then boost the rent. For those struggling with cheap homeownership, that stinks.

Under the new, earthshakingly equitable law, some Maine trailer tenants have now banded together to buy their property, The New York Times reported October 10. “The residents of Linnhaven Mobile Home Center, a community of nearly 300 occupied homes in Brunswick…paid $26.3 million to buy the property…by cobbling together loans and grants.” So rich investors won’t be grabbing THAT trailer park and jacking up the rent. Make no mistake, this is a win for the poor and middle class and one that, hopefully, will be repeated throughout Maine. Several states, including New York and Connecticut already have laws like Maine’s. With any luck, other states will follow this exemplary lead by passing similar legislation.

It’s desperately needed. That’s because plutocrats, obscenely rich investors and that bane of ordinary people’s lives, private equity firms, having gutted the land of its industrial base and manufacturing jobs, now feast on the population’s basic survival necessities: food, shelter and medicine. If you’ve had any experience of private equity snapping up a medical practice, you know this is not a good thing, as it becomes impossible to reach doctors by phone, you have to schedule appointments months out and costs skyrocket. Our billionaire aristocrats have already squeezed a fortune out of the housing market, which is why over 15 million homes sit empty—roughly five times the number of destitute homeless citizens. And why do they sit empty? Because they’re a good investment, even uninhabited, in a country that recalcitrantly refuses to acknowledge housing or medicine as a human right. At least we have food stamps—amirite?

So in some states, legislators attempt to protect their trailer park constituents from neo-feudal predation. But those states without such protections better hurry up and get them: “Between 2015 and 2022, around 800,000 manufactured housing [trailer] communities were sold to private equity investors and real estate investment trusts, more than a quarter of the total estimated number of manufactured home parks across the country.”

In a nation where half the citizenry cannot afford a sudden $1000 expense, while one billionaire, Elon Musk, is on track to become the world’s first trillionaire, the proles need all the help they can get. Otherwise, one calamity sends them hurtling to society’s rock bottom, because there is no social safety net. Most people who live in trailers own cars, so it’s a good bet that if a wealthy investor boots them out of their home, and they can’t double up with family or friends, they’d wind up living in their vehicle. No one knows how many Americans sleep in cars, but it’s not an insignificant number. And God forbid they need their transmission replaced, because then it’s straight to the homeless shelter for them or, barring that, sleeping under the stars.

Getting organized helps, too. Whether it’s going on a rent strike in a Staten Island, New York apartment building or doing what the Linnhaven trailer residents did, without such solidarity tenants with precarious housing are sunk. At Linnhaven, “they created a board of directors and went to work immediately after they learned that their landlord had received an offer from an outside investor to buy the park. When residents voted on the deal in August, not a single no vote was cast.” (I mean honestly, who’s going to vote “no, let the aristocrat triple my rent”?)

The larger real estate picture is grim. The median August price of a single-family home in Maine was almost $415,000, “but in 2019, it was around $230,000.” That’s confiscatory inflation. And it’s not just in Maine—it’s a catastrophically widespread American phenomenon. Even trailer prices have soared: “Between 2017 and 2022, the average price for a mobile home went up from $71,900 to $127, 300.” Townhomes offer a cheap alternative for those who can’t afford single family homes, and builders are catching on, the Washington Post reported October 21. But only 22 percent of US abodes are townhomes, and we need 3 to 7 million more domiciles in the U.S. If townhomes can provide this affordable housing, what the Post calls “the missing middle,” great. Developers have figured this out and hopefully the next white house resident will too—by making it worth while for real estate firms to finance this cheaper home-ownership alternative. But while we wait for townhomes, we’re in a national housing crunch.

Meanwhile, it’s no surprise adjunct professors continue to live in their cars, when universities behave like feudal lords. For instance, the University of California system “is trying to demand DEBT PAYMENTS from UAW students who went on strike last spring, claiming overpayment of wages,” tweeted the Debt Collective’s Astra Taylor on October 14. But according to a thread she posted, the university “cannot start overpayment recovery without your consent…State law is exceedingly clear on this matter.” And “the repayment cannot exceed 25 percent of your net disposable…income.” So if the workers elect not to repay, that’s fine, because any repayment must be voluntary. Again, in California as for the Maine trailer park residents, state law rides to the rescue.

So it’s no wonder that years ago, rich corporations that contribute to that aggressively grabby organization, Koch-funded ALEC, painted a target on state legislatures. That’s where the action is when it comes to extracting the last penny from Americans drowning in debt: remedies flow from state legislatures more reliably than those from Washington, which are a political football to be kicked off the white house lawn every four years when a new batch of rich donors seize control. But tragically, ALEC was very effective—red state legislatures enacted loads of reactionary laws promoting corporate interests over those of ordinary people—although their climate-denying ukases will ultimately cause even plutocrats to suffer. (That’s cold comfort to the low- and moderate-income denizens of Hurricane Alley, where climate-induced freak weather means they can no longer obtain homeowner’s insurance and thus could lose everything in the next storm.)

Our absurdly financialized economy has metastasized into something deadly for most people, as it dispossesses them of their trailer homes, their medical care and, for university employees, their wages. That financialization decimated the American manufacturing sector years ago, sending those good jobs first to Mexico (thanks, Bill Clinton), then to China, now to Bangladesh. So Americans adapted by living in debt. But eventually the creditor comes knocking, even as financial predators roam the land, plundering trailer parks, medical clinics and practices and anything else the humble rely on for survival. But as Maine shows, an occasional good law is enough to thwart the wicked who seek to dispossess them.

Eve Ottenberg is a novelist and journalist. Her latest novel is Booby Prize.

Source: counterpunch.org, October 25, 2024.