Published in issue no. 221, September 2020

By Darren Byler and Carolina Sanchez Boe

When Gulzira Aeulkhan finally fled China for Kazakhstan early last year, she still suffered debilitating headaches and nausea. She didn’t know if this was a result of the guards at an internment camp hitting her in the head with an electric baton for spending more than two minutes no the toilet, or from the enforced starvation diet.

Maybe it was simply the horror she had witnessed—the sounds of women screaming when they were beaten, their silence when they returned to the cell.

Like an estimated 1.5 million other Turkic Muslims, Gulzira had been interned in a “re-education camp” in northwest China. After discovering that she has watched a Turkish TV show in which some of the actors wore hijabs, Chinese police had accused her of “extremism” and said she was “infected by the virus” of Islamism. They predicted it would lead her to commit acts of terrorism, so they locked her away. Gulzira’s detention lasted more than a year. She was released in October2018, only to be told that she has been assigned to work in a glove factory near the camp. After long hours behind a sewing machine, Gulzira was kept in a dormitory surrounded by security checkpoints that used facial-recognition technology to track her movements and scraped data from her smartphone, which she was required to carry at all times. She was paid $50 a month, roughly one-sixth of the legal minimum wage in the region.

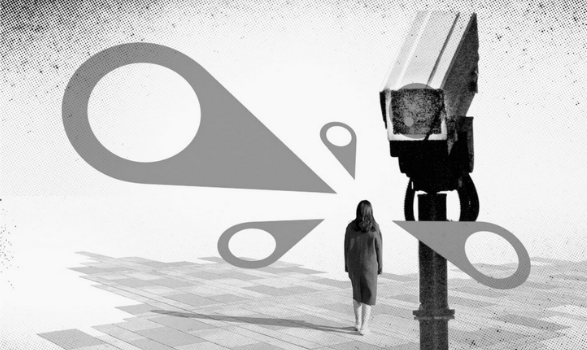

Gulzira was one of the millions of targets of a global phenomenon we call “terror capitalism.” Terror capitalism justifies the exploitation of subjugated populations by defining them as potential terrorists or security threats. It primarily generates profits in three interconnected ways. First, lucrative state contracts are given to private corporations to build and deploy policing technologies that surveil and manage target groups. Then, using the vast amounts of biometric and social media data extracted from those groups, the private companies improve their technologies and sell retail versions of them to other states and institutions, such as schools. Finally, all this turns the target groups into a ready sources of cheap labor—either through direct coercion or indirectly through stigma.

The people being targeted by terror capitalism include entire stateless groups, such as ethnic Bengalis in north-east India and Palestinian Arabs. They are almost always from minority or refugee populations, especially Muslim ones. While the Chinese system is unique in terms of its scale and the depth of its cruelty, terror capitalism is an American invention, and it has taken root around the world.

In China, the terror capitalism system targets many of the more than 15 million Uighurs and other Turkic Muslims in the region. Coercing these people in to low-wage work means fewer Chinese jobs move to Vietnam and Bangladesh. The companies that have developed China’s policing technologies are now selling them to police units and regional governments in Zimbabwe, Dubai, Kuala Lumpur, the Philippines and many other locations.

Meanwhile, across Europe and North America, terror-capital surveillance tools have places hundreds of thousands of Muslims on watchlists as part of Countering Violent Extremism programs. In the United States, immigration control measures taken in the aftermath of 9/11 have paved the way for a system that monitors and controls asylum seekers who enter the country at the southern border.

These systems use GPS tracking to control in ways that are similar to the surveillance system in north-west China. After being held in a US detention center, a Pakistani asylum seeker named Asma was required to wear a GPS-enabled ankle monitor. (More than 32,000 foreign nationals in the US have to so the same.) Asma told us how stigma associated with her ankle monitor pushed her into low-paid work. A food-truck owner in Austin, Texas, gave her a job because, he told her,the customers couldn’t see the monitor if she stayed behind the counter in the truck. But when the monitor started blaring, “Recharge battery! Battery low! Recharge battery! Battery low!” during her shift one day, her boss fired her. A year after Asma obtained asylum, her ankle is covered with scars from the monitor and she often feels phantom vibrations in her leg.

Ankle monitors are still prevalent, but in the past two years, US asylum seekers have also increasingly been made to submit to weekly “biometric check-ins,” through an app called SmartLink, which they are made to install on their phones. They have to keep their phones charged and GPS active at all times. Lorena, an asylum seeker who has fled violence in Guatemala, was initially relieved that her ankle monitor was removed, until she was required to give Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) access to her email account, which connects to her social media accounts.

The SmartLink app is now being used to control 21,712 immigrants. It was developed by BI Incorporated, a company that initially designed GPS ankle monitors. BI is now a subsidiary of Geo Group, one of the major prison and detention companies that have profited from a dramatic expansion of prisoner and detained populations in the US over the past four decades. The app is also supported by the nationwide telecom providers Sprint and Verizon, with movement tracking provided by Google Maps.

The rationale for these new regimes of technological surveillance and control emerged directly from the “global war on terror” that the George W. Bush administration declared in 2001. So too did early versions of many of the policing technologies now being used around the world. The new paradigm began in Iraq, where counter-insurgent war demanded a suspension of civil and human rights that allowed the US army to identify and track the movements, online activities, networks, and states of mind of masses of Iraqis. China eventually followed suit, with Xi Jinping justifying the technological subjugation of the country’s Muslims by declaring the “people’s war on terror” in 2014.

“Surveillance is about controlling and disciplining marginalized people—whether it’s people of color, immigrants, or poor people,” says a current employee of Microsoft, which was a key early-stage investor in AnyVision, an Israeli surveillance technology company that has used facial recognition to monitor Palestinians in the West Bank. “Companies use surveillance to reinforce systemic racism and perpetuate mass incarceration. States use surveillance to enforce border logics and state oppression. Surveillance, as a concept, isn’t neutral—it is always about control.”

Because terror capitalism emerges at the nexus where the power of states such as the US and China meets the power of tech companies such as Microsoft, Google, Hikvision and SenseTime, fighting it will require not only an empowered public but also peoplewithin governments and companies to regulate and resist harmful forms of surveillance. There is a growing movement among tech workers, from Seattle to Hong Kong, who are appalled by the complicity of their employers in terror capitalism. Together with them, we must push these companies to refuse to profit from the militaristic ambitions of these states.

Lorena’s and Asma’s names have been changed to ensure their anonymity.

Dr Darren Byler is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Colorado. Dr Carolina Sanchez Boe is a Danish Research Foundation postdoctoral fellow.

Source: theguardian.com, July 24, 2020

Be the first to comment on "Tech-enabled Surveillance Capitalism Is Spreading Worldwide"